The closure of Censorship Is the Curator (of This Exhibition) in Escaldes-Engordany highlights, once again, the persistence of censorship and the ease with which political intervention—justified under a discourse of “security”—can erode the democratic foundations of artistic practice. This episode reinforces the urgency of articulating affirmative resistance from within the cultural field and compels us to interrogate the contemporary mechanisms of silencing.

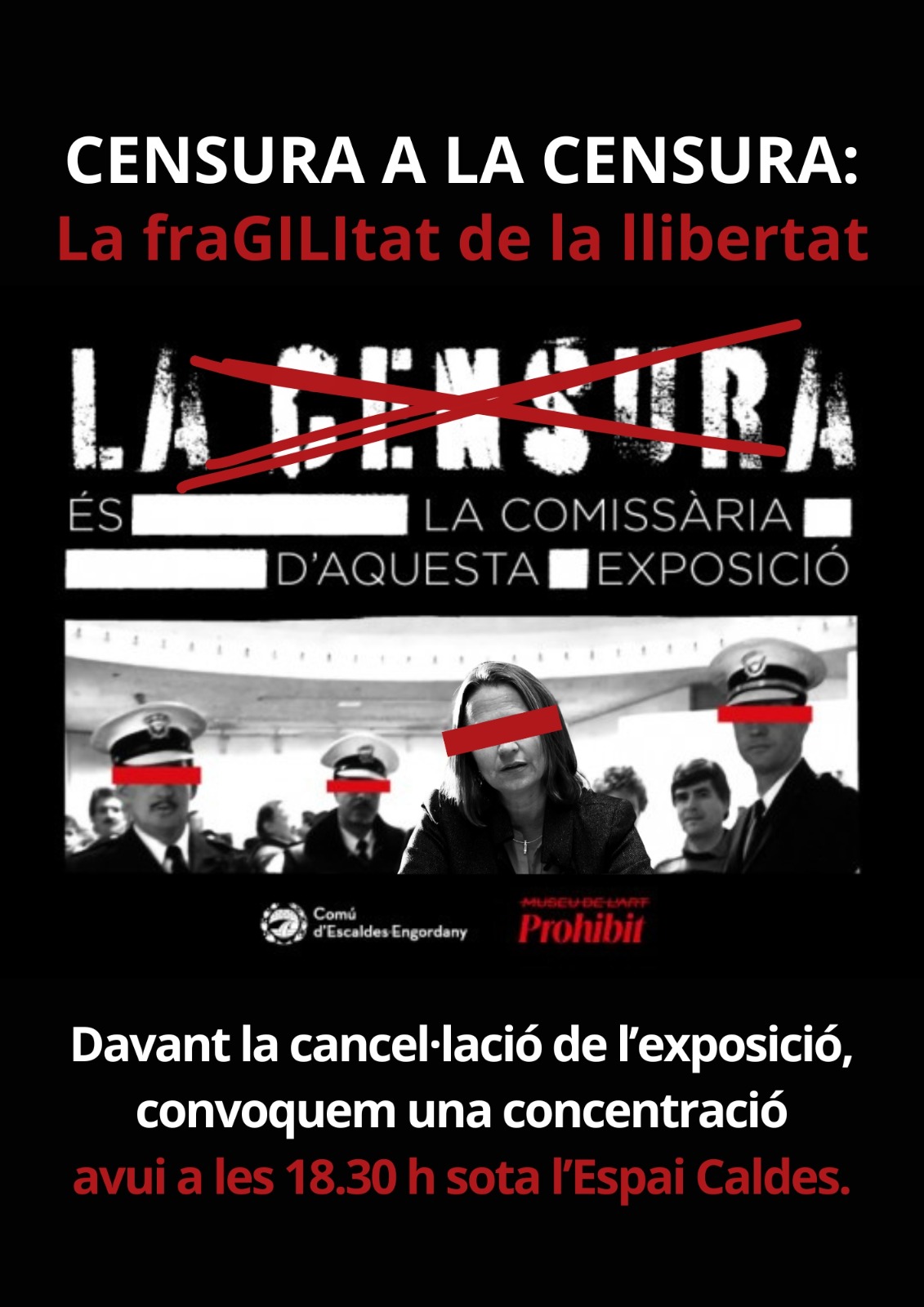

The forced shutdown of the exhibition, mere minutes after the opening of the first touring show of the Museu de l’Art Prohibit, is not an anecdotal event, but part of a permanent state of exception that is activated each time a work challenges dominant sensitivities. John Stuart Mill warned in On Liberty (1859) that “if all mankind minus one were of one opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.” When the silenced subject is a group of artworks—and, by extension, the audience—the cognitive loss affects society as a whole. Michel Foucault described modernity as a “general economy of danger” (1976), a dispositif that enables the sovereign to invoke indefinite threats and restrict freedoms. In the Andorran case, the removal of a Charlie Hebdo cover by the mayor of Escaldes-Engordany, Rosa Gili, under the pretext of a terrorist risk, exemplifies that logic: the supposed protection of citizens serves to curtail their right to engage with that which might unsettle them.

The exhibition, conceived by curator Carles Guerra, was structured as a choral narrative in which each piece touched on a historical form of prohibition, veto, or silencing. My installation Picasso comunista, composed of 196 documents from the declassified dossier on Pablo Picasso—spied on by the CIA due to his membership in the French Communist Party—was presented alongside works by Ai Weiwei, Paul McCarthy, Marcelo Expósito, Mounir Fatmi, Marta Minujín, among others. The show derived its meaning precisely from the friction between these varied cases. To remove a single work, as Guerra aptly stated, “undermines the entire exhibition.” A museum intended to explore the many dimensions of censorship and prohibition was thus turned into a living example of what it sought to denounce.

Susan Sontag defined self-censorship as “the most effective form of silencing” (At the Same Time, 2007), and the Andorran intervention demonstrated the interaction between direct prohibition and internalized control. Banning an image does not merely erase it from discourse—it creates a climate of fear that leads programmers and creators to adopt anticipatory restraint.

Mill insisted that only the prevention of direct harm to others justifies limiting expression; mere offense or discomfort does not meet that threshold. George Orwell echoed this in 1945: “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” Yet when the cultural sphere is framed as a security issue, and art placed on par with imminent threat, the possibility of critical dialogue is neutralized. It entrenches the idea that certain images are, by definition, unacceptable.

Jacques Rancière has stated that the emancipatory function of art lies in the redistribution of the sensible, not in obeying orders. Toni Morrison, in her Nobel lecture (1993), warned that “censorship mutilates speech, and therefore experience.” Where language is restricted, thought narrows, and democratic deliberation weakens.

This incident challenges cultural institutions to clarify how they will defend their autonomy against political interference. Outrage alone is insufficient; there must be binding protocols to prevent unilateral modification of approved projects, mechanisms to document and publicize censorship in real time, and networks of artistic solidarity committed to collective action that raises the political cost of any ban.

Artists today face the dual threat of prohibition and self-censorship. To sustain a dissident voice requires institutional support, solidarity among peers, and legal guarantees. Each time a work is suppressed, the public loses a space for critical engagement, and the common stock of ideas is impoverished.

In the face of censorship, the response must be deliberate and sustained: to expose its mechanisms, name those responsible, and weave solidarities that restore the right to cultural dissent. The pieces banned in this exhibition assert that essential space of friction where hegemonic narratives are unsettled. As Foucault noted, “power’s success is proportional to its ability to hide its own mechanisms.” Our task, as artists and citizens, is to make those mechanisms visible—and to rehearse collective forms of resistance that overflow the boundaries set by censors. Only then can we contest the present and affirm that art is not a rhetorical luxury, but an essential exercise in freedom.

Leave a Reply