The recent debate about the validity, function, and future of the museum—rekindled by the publication of Francesc Torres’s article “The Winter Palace Is Somewhere Else” and the responses it has triggered—has settled, with almost anesthetic ease, into a false battlefield. We seem forced to choose a trench in a binary war of positions: either we defend the museum as we know it, an immovable civilizational bulwark, or we call for its festive demolition in an act of cultural nihilism. The real problem, however, does not lie on that inflamed border or in that caricature of irreconcilable camps. The thesis advanced here is another—simpler, less epic, and therefore much more uncomfortable: the museum is not going through a crisis of usefulness, but a crisis of model. This is not a blanket repudiation of its existence, but a severe diagnosis of its metabolism. The task is not to knock down the building; it is to pass through it with a criticism that acts like a current of air in an organism now at risk of suffocating in its own inertia, and to reposition it—humbly and urgently—within a multiple, living, and complementary institutional ecology.

If there is an “enemy” in this equation, it is not the museum as a concept, nor the collection as a device of memory: it is the bureaucratic inertia that renders it irrelevant to vast segments of society, the budgetary capture that leaves crumbs for programming and mediation while fattening line-items for security and the upkeep of empty containers, and the structural precarity that systematically expels those who sustain cultural life. What this landscape of attrition calls for is neither nostalgia nor corporatist self-defense, but capital-letter cultural policy: rules, metrics, funding, and a will to transform.

First of all, we should defuse a recurrent analogy often used to shield the institution from scrutiny: the notion that criticizing the museum amounts to negating it, just as questioning democracy would imply wishing for its abolition, or rethinking the book would herald the death of literature. This comparison is intellectually dishonest. Institutions that endure—from parliamentary democracy to the university—do so precisely because they acknowledge their revisability; they survive by mutating, by changing procedures, correcting historical biases, and opening new channels of public oversight. The book moved from scroll to codex to screen; democracy expanded suffrage and civil rights. To armor the museum against radical critique under the pretext of protecting it does not save it; it crystallizes it. It turns it into an archaeological object ahead of its time. An institution that conceives of itself as a temple ends up confusing itself with its fortified perimeter; an institution that recognizes itself as process understands that its legitimacy does not reside in the grandeur of its foyer, but in how it decides, whom it benefits, which voices it amplifies, and what value it returns to the community that funds it.

The current political climate adds another layer of urgency that we cannot afford to ignore. Culture has become a battleground within a global reactionary wave that barely hides its intentions: bans on artists are normalized, educational programs addressing gender or memory are cut, and a counterfeit “neutrality” is demanded—as if neutrality were not, in itself, a taking of sides for the existing order. In such a hostile context, the institution that declares itself apolitical, that retreats into the ivory tower of abstract “excellence,” merely operates the status quo and becomes vulnerable. The alternative is not to turn the museum into a pamphlet or a party headquarters, but to deepen cultural democracy: open governance procedures, expand critical mediation, guarantee labor rights, share decision-making power, and create conditions in which dissent is possible. A museum understood as a porous public infrastructure, rather than a fortress guarding treasures, is infinitely better equipped to withstand the culture war without becoming its hostage.

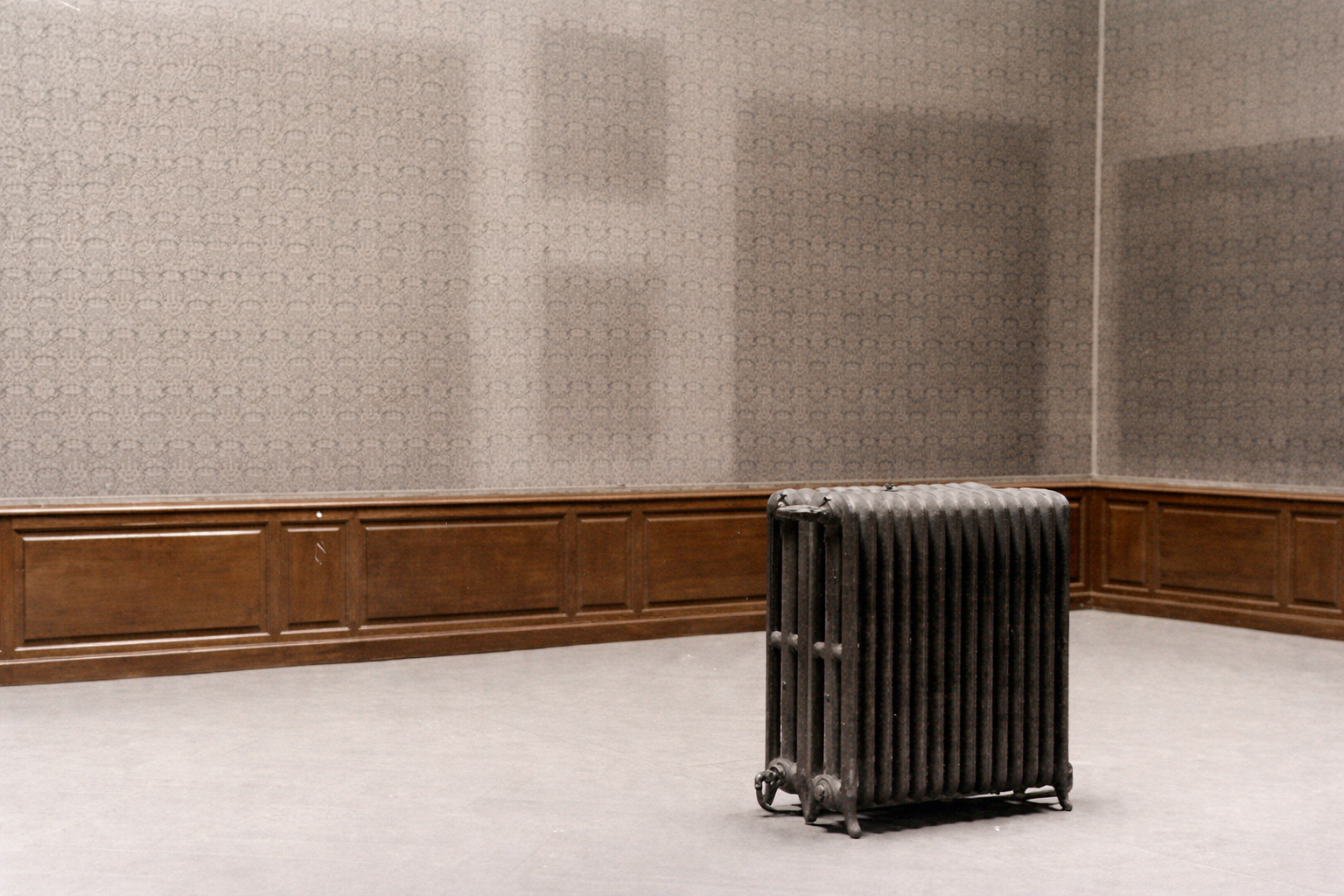

It is true that acknowledging the museum’s history and achievements is an act of justice. This is not about erasing the past. For two centuries, the museum organized memory, knowledge, and aesthetic pleasure with extraordinary effectiveness; it built national narratives and preserved patrimonies that would otherwise have dispersed. It is equally true, however, that in the same movement it consolidated exclusionary hierarchies, canonized patriarchal and colonial perspectives, and armored a regime of legitimacy that is now springing leaks. That legacy now coexists with a present in which the museum’s monopoly over artistic legitimacy no longer holds. And that monopoly is waning not because the museum “dies,” but because the cultural ecosystem has diversified and grown richer. When the museum ceases to be the form and becomes one form among others, the entire ecosystem benefits: process and production centers, living archives in use, pedagogical laboratories, open digital platforms, community museums, and extra-mural practices. The relevant question of the twenty-first century is no longer “museum yes or no,” but how functions and responsibilities are distributed within a polycentric ecology that accommodates memory and sustained study alongside living production, trial and error, critical mediation, and open documentation. Less architectural icon, more social process.

This transition inevitably demands a different political economy. The museum of contemporary art suffers from a chronic, pathological exposure to the market–event–visibility triad. We have built a perverse incentive system: when the dominant metric for evaluating the success of a director or a cultural policy is immediate media impact or the raw number of bodies through the turnstile, energy and funding shift away from research, mediation, and care (the invisible) toward quantifiable spectacle (the visible). Correcting that bias is not a matter of curatorial rhetoric but of hard regulatory architecture: we need to separate indicators of public interest from the price-setting logics of the art market; set minimum percentage thresholds for artists’ and mediators’ fees; incorporate binding ethical clauses into sponsorships; and open non-market commissions and networked circulation that do not depend on fairs or auction houses. Public money must reach the work, the research, and the public—not get lost in the inertia of an overgrown administrative apparatus or in exorbitant insurance for trophy pieces.

This is not about promising the impossible or lapsing into naive utopianism, but about writing what we might call institutional prose. Against the poetry of lofty statements on beauty and heritage, we need the prose of bylaws. Shared governance with hard rules: quorums, accessible public minutes, a registry of conflicts of interest for boards and acquisition committees. A percentage of the program subject to binding decision by external juries or citizens’ assemblies; a lean fixed structure that allows most of the budget to be devoted to commissioning, production, and activity; standard contracts that eliminate precarity and payments on reasonable timelines. Comprehensible indicators that measure real social and territorial impact, effective accessibility (not only physical, but cognitive and economic), interaction time and quality of work—beyond the tyranny of clickbait or the queue at the ticket desk. Sustainability must become method, not a green label: less ephemera, more extended temporalities; systematic reuse and reasonable logistics; accessibility as a design criterion from minute one; open documentation as a rule of public return. Taken together and applied rigorously, these decisions change the institutional metabolism far more than any avant-garde manifesto.

A model critique does not prescribe a single form, but a constellation. A museum of memory, conservation, and deep study (the “Palace” that stores and cares) can and should coexist with agile process devices that commission, mediate, and document contemporary creation without the heaviness of marble. That coexistence does not duplicate efforts; it distributes and specializes them. It minimizes unnecessary overlaps, diversifies available narratives, spreads the risks of cultural commitment, and improves public service. A polycentric ecology is, above all, an exercise in institutional humility: accepting that no institution, however venerable, can be everything to everyone, and that contemporary legitimacy is built cooperatively in networks, not by ferociously competing for the same headline or the same grant.

Those who fear that this evolution will “destroy what we have,” or argue that we must first solve the storage problems of large museums before indulging in “experimental luxuries,” confuse stability with paralysis, and management with political imagination. The truly conservative responsibility, in the noblest and etymological sense of the term—to conserve what deserves to endure—is to ensure that institutions have a future, not that they remain identical to their past. A full warehouse does not replace a living commissioning policy; a shielded organizational chart does not equal professional excellence; an architectural expansion without a clear program contract is an end in itself—a monument to ego, not a cultural tool. The opposite of empty grandiloquence is operational detail: rules of the game, budget percentages, realistic calendars, public reports, social impact audits. To govern—in culture as in everything—is to explain how decisions are made and to assume responsibility for them.

To label this demanding reformist agenda “infantile” or accuse it of tabula-rasa daydreaming is a dialectical convenience, a rhetorical refuge for avoiding the complexity of the moment. Infantile is to demand international excellence while refusing to touch ossified structures; infantile is to ask for first-division collections with operating budgets that leave crumbs for actual programming; infantile is to invoke the neutrality of art amid mechanisms of censorship; infantile is to grant the market the last word on what counts as value while scolding those who question its success indicators. Adulthood, institutionally speaking, is to negotiate the rules of conflict, to have the courage to shift the budget toward where creative life actually happens, to accept that culture is a field of tensions, and to measure results honestly. Adulthood is to admit that the museum does not need to be rescued from critique as if it were a helpless victim; it needs to be traversed, shaken, and fertilized by critique in order to remain a relevant public space of meaning.

The conclusion, though expansive in its implications, fits into a few lines of political intent. Let us defend the museum, by all means, but let us once and for all abandon its monopoly and sacred exceptionalism. Let us defend conservation and rigorous study, but with equal force demand that public money reaches the production of the living, mediation in neighborhoods, the documentation of the ephemeral, and the care of those who work. Let us defend excellence, but only if it is backed by clear rules, transparency, and ongoing public evaluation. Let us defend the artwork, but within objectives, indicators, and tangible social returns. What is proposed here is not mindless demolition, but high-precision surgery: open windows, air out offices, redistribute resources, measure impacts, care for people. In times of identitarian retreat and simplifying polarization, the museum cannot afford to be an isolated, self-complacent bastion: it must become a living organ within a broader, more diverse institutional body. Only thus—acknowledging itself as one form among others in a plural concert—will it continue to fulfill its fundamental function: to guarantee a society’s inalienable right to think itself, argue itself, contradict itself, and imagine itself in common.

Leave a Reply