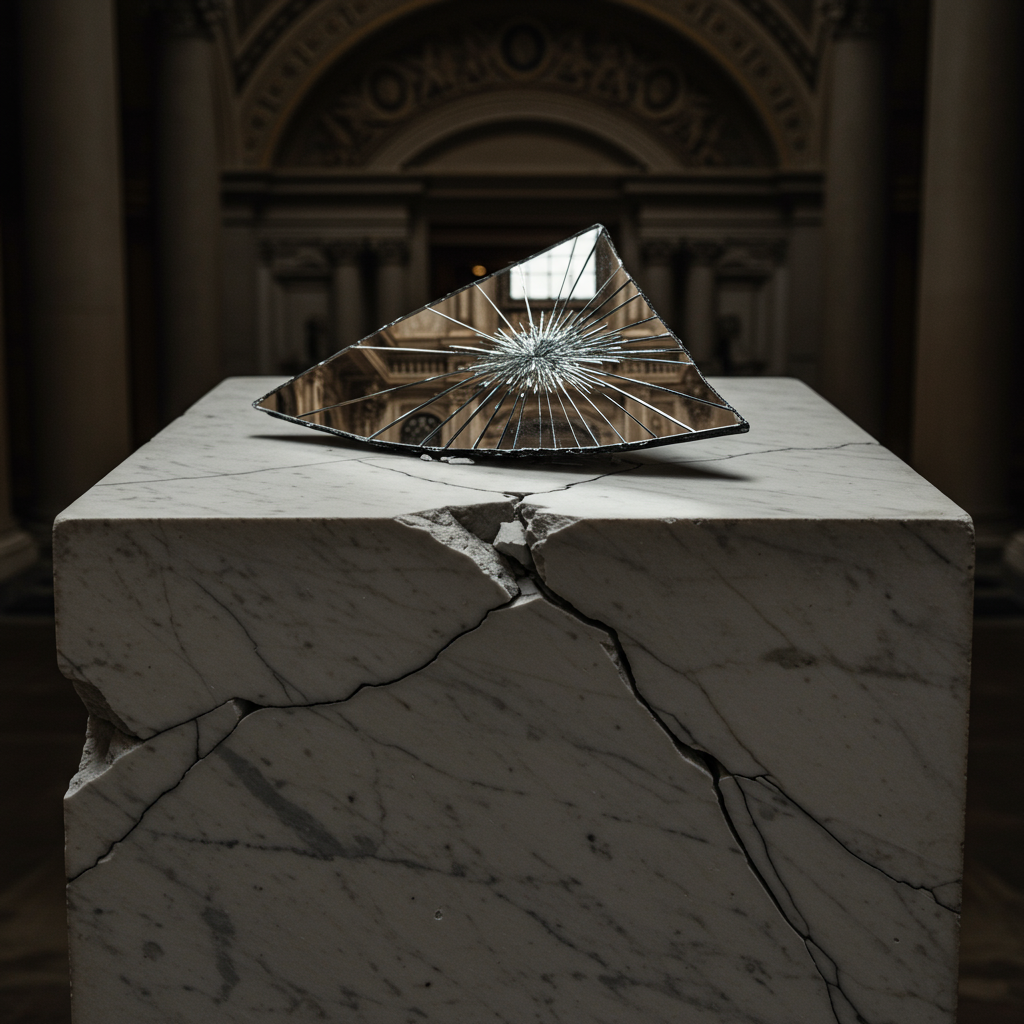

In contemporary imaginaries, few figures inspire as much admiration as the radical artist—the creator who defies established forms, dismantles dominant narratives, and positions themselves at the margins of convention to open new horizons of meaning. The art that breaks rules, unsettles, and impugns is often seen as the art we most urgently need.

Daniel G. Andújar junio 2025 ES. version

But we rarely ask: who can afford to break?

The history of art, critical thought, and cultural avant-gardes is filled with disruptive figures whose trajectories cannot be understood apart from their material conditions. Often, those who have been able to practice the most radical forms of experimentalism, who have turned risk into an aesthetic, came from privileged positions: inherited wealth, social networks, economic, symbolic, or racial capital. Their radicality was not only a matter of genius; it was also a matter of structural possibility.

This is not a moral critique, nor does it aim to diminish the value of such works. But it does demand that we expand the frame to recognize that what often appears as aesthetic freedom is, in fact, conditional freedom. That the gesture of breaking the narrative, dismantling linearity, and wagering on subtraction, on emptiness, and on anomaly is inscribed within a context of access.

And here we are not only talking about class. We are also talking about gender, race, sexuality, and embodiment. Because risk is not distributed equally.

When rupture comes from masculine, white, elite cultural bodies, it is often read as genius, innovation, or avant-garde. But when it comes from feminized, racialized, or dissident bodies, it is often read as a threat, error, marginality, caprice, lack of professionalism—or simply erased. The history of art and cinema is full of figures who never reached the place of the “great innovator” simply because they were never admitted into the canon of risk.

Breaking language does not mean the same for everyone. A wealthy white man who destroys a mural is a conceptual hero; a racialized woman who challenges representational codes may be disqualified, expelled from circuits, ridiculed, or erased from the archive. For some, exceptionality is celebrated transgression; for others, it is a place of precarity, punishment, and invisibility.

Moreover, we must ask: what does it mean to break when one has never been included? For many bodies and subjectivities, the problem is not how to dismantle the dominant narrative but how to enter it, how to inhabit it without being crushed. When representational frameworks already exclude you by race, class, gender, disability, or geography, the gesture of impugning norms is not always an aesthetic option—it is an existential condition.

This is why it is not enough to admire those who have been able to break from above. We must also look toward those who have been breaking from below, without cameras, without collections, without retrospectives, and without awards. Toward those who cannot afford experimentalism because they live under survival regimes. Toward those who do break, but do so outside systems of cultural legitimization, or who are dismissed as “too political,” “too uncomfortable,” “too literal,” “too feminist,” “too Black,” or “too poor.”

Artistic experimentalism—like theoretical inquiry, like political dissent—often requires precarity, but also the ability to sustain it. It is not the same to fail when one has family, patrimonial, or symbolic networks as it is to fail when one comes from the margins, when what is at stake is not prestige but survival. Some wager their name; others wager their body. Some break symbolic frameworks; others have never even been included within them.

The question is not just who breaks, but who pays the price of breaking. How much of what we call rupture is, in fact, a prerogative of privilege? How much of the freedom to impugn depends on prior security, on guarantees of return, on an assured place within legitimizing circuits? And further: how many other forms of dissent never inscribe themselves within the cultural field because there is no one to support, amplify, or legitimize them?

The risk is clear: that we end up confusing exception with rule, anomaly with universal possibility. That we celebrate the dissent of those who can afford to play at the edges, while ignoring those who are thrown beyond any edge. That we transform the gesture of rupture into a market fetish, an exhibition product, a cool identity.

At its core, what is at stake is not just art, politics, or thought; it is the question of the material conditions of freedom. Who has the right to error? Who can withstand risk? Who can challenge codes without disappearing in the attempt? Who can fail beautifully—and who cannot even afford to try?

From below, risk is not just symbolic failure. It is the risk of disappearance. It is the risk of having nowhere to return to. It is the risk of no one ever calling again.

The urgent challenge is not only to celebrate art that impugns but also to ask how to broaden the material conditions that make it possible. How to ensure that aesthetic freedom is not a privilege, that risk does not depend on social armor, that dissent is not a prerogative of normative bodies. How to open spaces so that experimentalism is neither a luxury nor an exception celebrated only when it comes from certain places, but a possibility that is distributed, contaminated, interrupted, and reclaimed.

The task is twofold: to sustain the value of rupture, yes, but also to think about how to redistribute the conditions that make rupture possible. Not to demand abstract equality—as if we all had to break in the same way—but to imagine ways to share risk, democratize dissent, and expand the field of those who can inscribe themselves into the history of anomalies.

Because if exceptionality is always privilege, the question is no longer just what is being broken, but who continues to hold up the ground that others leap from.

Leave a Reply